- Joined

- Dec 28, 2009

- Messages

- 288

- Points

- 63

phys.org

Jul 22, 2014 by Brian Doctrow

Creating optical cables out of thin air

Jul 22, 2014 by Brian Doctrow

Creating optical cables out of thin air

Imagine being able to instantaneously run an optical cable or fiber to any point on earth, or even into space. That's what Howard Milchberg, professor of physics and electrical and computer engineering at the University of Maryland, wants to do.

In a paper published today in the July 2014 issue of the journal Optica, Milchberg and his lab report using an "air waveguide" to enhance light signals collected from distant sources. These air waveguides could have many applications, including long-range laser communications, detecting pollution in the atmosphere, making high-resolution topographic maps and laser weapons.

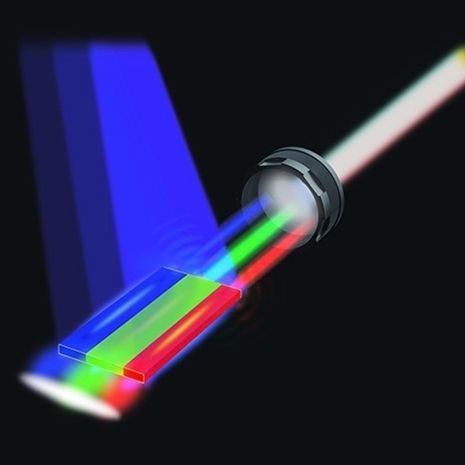

Milchberg's air waveguides consist of a "wall" of low-density air surrounding a core of higher density air. The wall has a lower refractive index than the core—just like an optical fiber. In the Optica paper, Milchberg, physics graduate students Eric Rosenthal and Nihal Jhajj, and associate research scientist Jared Wahlstrand, broke down the air with a laser to create a spark. An air waveguide conducted light from the spark to a detector about a meter away. The researchers collected a strong enough signal to analyze the chemical composition of the air that produced the spark.

The signal was 1.5 times stronger than a signal obtained without the waveguide. That may not seem like much, but over distances that are 100 times longer, where an unguided signal would be severely weakened, the signal enhancement could be much greater.

Milchberg creates his air waveguides using very short, very powerful laser pulses. A sufficiently powerful laser pulse in the air collapses into a narrow beam, called a filament. This happens because the laser light increases the refractive index of the air in the center of the beam, as if the pulse is carrying its own lens with it.

Milchberg showed previously that these filaments heat up the air as they pass through, causing the air to expand and leaving behind a "hole" of low-density air in their wake. This hole has a lower refractive index than the air around it. While the filament itself is very short lived (less than one-trillionth of a second), it takes a billion times longer for the hole to appear.

Importantly, the "pipe" produced by the filaments lasted for a few milliseconds, a million times longer than the laser pulse itself. For many laser applications, Milchberg says, "milliseconds is infinity."

Last edited: